Recent scientific findings suggest that Neanderthal genes make up about 1 to 4 percent of the genome of modern humans whose ancestors migrated out of Africa, but the extent to which these genes still actively influence human traits remains an open question—until now.

A multi-institutional research team including Cornell has developed a new set of computational genetic tools to address the genetic effects of interbreeding between non-African humans and Neanderthals that occurred about 50,000 years ago. (The study only looked at descendants of those who migrated out of Africa before the Neanderthals died out, specifically those of European ancestry.)

In a study published in eLife, the researchers report that some Neanderthal genes are responsible for certain traits in modern humans, including several with significant effects on the immune system. Overall, however, the research shows that modern human genes prevail over successive generations.

“Interestingly, we found that several of the identified genes involved in modern human immune, metabolic and developmental systems may have influenced human evolution after the ancestral migration out of Africa,” said study co-author April (Xinju) Wei , assistant professor of computational biology in the College of Arts and Sciences. “We have made our custom software available for free download and use by anyone interested in further research.”

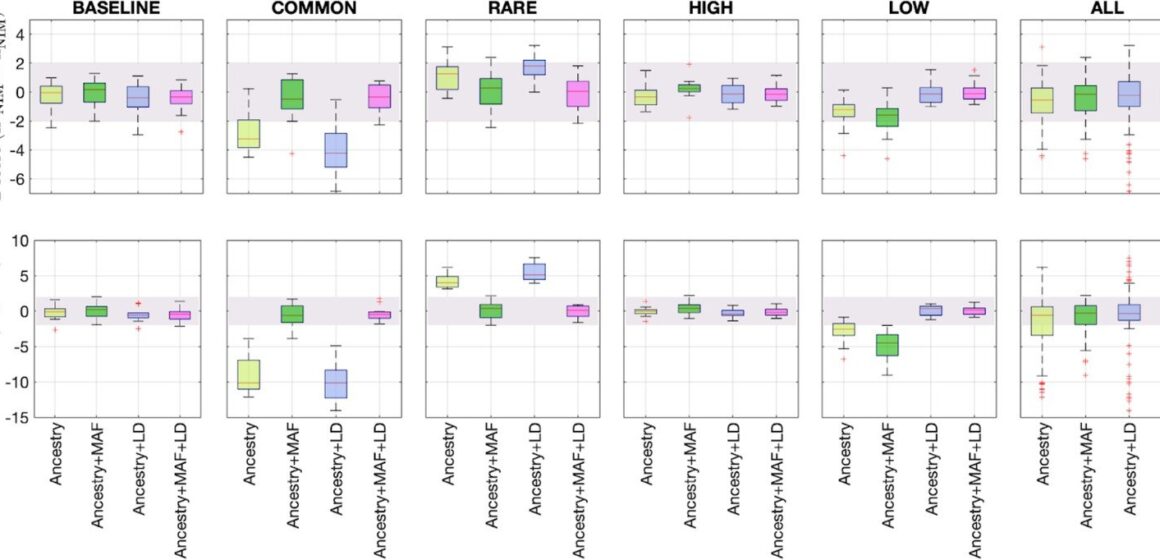

Using a huge dataset from the UK Biobank, consisting of genetic and trait information on nearly 300,000 Britons of non-African descent, the researchers analyzed more than 235,000 genetic variants likely to have originated in Neanderthals. They found that 4,303 of these DNA differences play a significant role in modern humans and affect 47 different genetic traits, such as how fast someone can burn calories or a person’s natural immune resistance to certain diseases.

Unlike previous studies, which could not completely rule out genes from modern human variants, the new study used more precise statistical methods to focus on variants attributed to Neanderthal genes.

While the study used a dataset of almost exclusively white individuals living in the UK, the new computational methods developed by the team could offer a way forward in gathering evolutionary insights from other large databases to delve into the genetic influences of archaic humans on modern humans.

“For scientists studying human evolution who are interested in understanding how interbreeding with archaic humans tens of thousands of years ago still shapes the biology of many modern humans, this study can fill some of those gaps,” said senior researcher Sriram Sankararaman, associate professor at the University of California, Los Angeles. “More broadly, our findings may also provide new insights for evolutionary biologists looking at how echoes from these types of events can have both beneficial and harmful consequences.”

More info:

Xinzhu Wei et al, The lasting effects of Neanderthal introgression on human complex traits, eLife (2023). DOI: 10.7554/eLife.80757