‘Pro-Russian neutrality’: how Ukraine sees China’s emerging role

Kyiv, Ukraine – Volodymyr, an emaciated 44-year-old man, recently returned from the Eastern Front in Ukraine and now needs psychological help for his post-traumatic stress disorder.

A concussion causes him to stutter slightly.

He voraciously reads the news on the broken screen of his mobile phone and has a strong opinion about the recent headlines about the role of China, the only remaining heavyweight partner in Russia’s corner, in the war.

“China prefers to stay out of this mess,” Volodymyr tells Al Jazeera, withholding his last name because he is still on active duty. “They will never openly support Russia.”

“Openly” is a keyword.

As the Russo-Ukrainian war approaches its 15th month, China still regards President Vladimir Putin as an irreplaceable “strategic” ally.

Chinese President Xi Jinping remains the only world leader who maintains friendly ties with Putin, and has used China’s seat on the United Nations Security Council to repel diplomatic attacks on the Kremlin.

Xi never denounced the war, rather calling it a “crisis.”

According to Ukrainian observers, Beijing’s position is full of ambivalence and omissions.

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin pose for a photo during their meeting at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia (File: Sergei Karpukhin/Sputnik/Kremlin via AP)

Chinese President Xi Jinping and Russian President Vladimir Putin pose for a photo during their meeting at the Kremlin in Moscow, Russia (File: Sergei Karpukhin/Sputnik/Kremlin via AP)According to some, Xi views the conflict through the prism of Taiwan, as China has long threatened to forcibly “unify” the autonomous island with the communist mainland in ways that may be similar to how Russia “returned” Crimea.

While he now appears to be trying to add a peacemaker feather to his cap, observers say he may in fact be trying to freeze the war on Russia’s terms to allow it to replenish its arsenals, train more military and shift its economy to war mode.

“China doesn’t need a pompous truce,” Sinologist Petro Shevchenko of Jilin University in the Chinese city of Changchun told Al Jazeera. “In principle, it will settle for some kind of freeze, when Ukraine does not declare an end to the war.”

Beijing has said Ukraine’s “territorial integrity” must be upheld, and in February proposed a 12-point peace plan that was met with skepticism by Western powers. While calling for dialogue and denouncing the possibility of nuclear escalation, the plan also criticized Western sanctions against Moscow and did not urge Russia to withdraw troops.

To convince Kiev, Beijing will “turn to economic statecraft, economic tools” that may include a contribution to Ukraine’s postwar restoration and better market access to China for Ukrainian food producers, Shevchenko said.

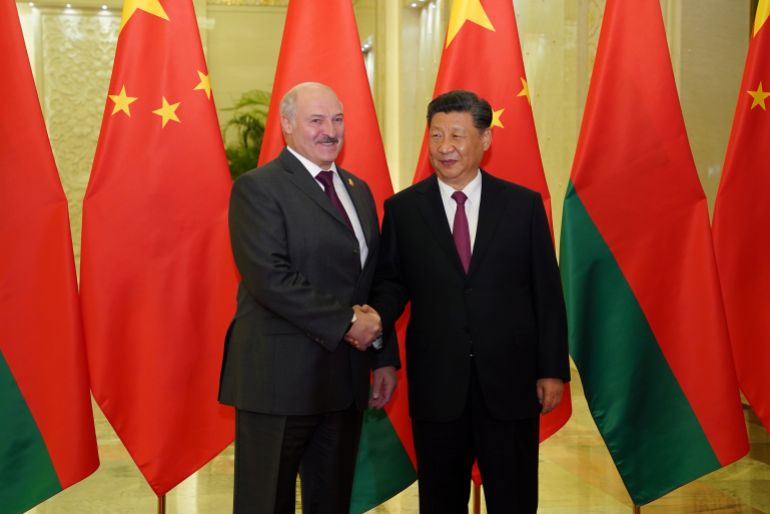

Xi shakes hands with Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko (File: Andrea Verdelli/Pool via Reuters)

Xi shakes hands with Belarusian President Alexander Lukashenko (File: Andrea Verdelli/Pool via Reuters)It could be easy.

In 2017, China became Ukraine’s largest trading partner. Buy wheat, corn, jet engines, and steel plates, among other things.

Beijing also wants Ukraine to become a hub for the mammoth Belt and Road infrastructure project that stretches across Eurasia from Pakistan to Poland, a role Kiev rejected after Russia’s 2014 annexation of Crimea.

But if Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy ignores China’s peace offer, Xi may start supplying Russia with weapons, including drones and microchips, Shevchenko said.

The move could be especially damaging given that many Chinese weapons are based on Soviet prototypes.

Beijing can also tacitly incite North Korea and Iran to send weapons and ammunition to Moscow, he said.

But the former senior diplomat from Ukraine believes that this is something that Beijing will not dare to do.

“China should not cross the line, otherwise it will face a lot of problems, not only economic, but also political,” Volodymyr Ohryzko, a former Ukrainian foreign minister, told Al Jazeera.

A profitable stagnation

Xi is not prolifically trying to push both sides toward a truce, preferring to bide his time without getting too involved in the conflict.

“Russia plays the role of an international bully that shakes up the world order. The US and China benefit from the process and will create a new (world order),” kyiv-based analyst Igar Tyshkevich told Al Jazeera.

China consumes Russia’s hydrocarbons, uses its territory as a springboard to European markets and craves the riches of the Arctic that Moscow cannot tap on its own.

The existing status quo, when Western sanctions isolate Russia and the collective West is deeply involved in the war, is “generally comfortable for Beijing,” says Temur Umarov, a sinologist and expert at Carnegie Politika, a Berlin-based think tank. .

“In this situation, the United States doesn’t have the scope to start a conflict with China, to find out what’s going on in China, to deal with it, while Russia has more and more to offer Beijing because it has no other options.” she told Al Jazeera.

China would not mind repeating the diplomatic success it had in March when it brokered a rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia.

But that happened because both sides wanted an agreement, Umarov said.

“Using the same optics in Ukraine is very difficult, because neither kyiv nor Moscow are ready for talks of any kind,” he said.

‘Vassalization’ of Russia?

Oleksandra Kurenenko, who teaches physics at a private school in kyiv, said that if China backs Russia “openly”, Russia will win the war.

But so far, “we are winning,” he said.

Beijing presents its position as “neutral”, but many in kyiv doubt the term.

“This is pro-Russian neutrality, as China implements Russia’s vassalage,” Alexander Merezhko, a senior foreign policy official at the Verkhovna Rada, the lower house of Ukraine’s parliament, told reporters in mid-May.

As Moscow faces spiraling economic isolation and diplomatic ostracism, its role as a global or even regional player is going downhill, with Beijing filling the void, including in Russia’s ex-Soviet territory from Central Asia to Belarus.

As the West reduces its reliance on Russian energy supplies and imposes draconian sanctions, Moscow is boosting exports of oil, gas, coal and timber to China, at cut prices.

Russia’s “minor” part in the alliance with China seems especially ironic given that it was Soviet Russia that played a key role in installing a communist government in Beijing in 1949.

Red Moscow also laid the foundation for China’s revival by providing key technologies from building iron smelters to developing a nuclear bomb.

Visits and sent

Xi visited Moscow in March but cut the trip short.

It also frustrated Putin’s expectations of signing deals on massive investment and the construction of a new natural gas pipeline to China.

Just a month after leaving Moscow, Xi called Zelenskyy, and the immediate result was minuscule.

Summing up their hour-long conversation, Zelenskyy tweeted about a “powerful boost to bilateral relations” and hailed the appointment of an experienced diplomat as special peace envoy to kyiv.

The diplomat, Li Hui, served as ambassador to Russia from 2009 to 2019. He is fluent in Russian, on friendly terms with Putin, and even received an award from the Kremlin chief.

But for kyiv, such knowledge of Russia is an advantage.

“Without a doubt, this man absolutely understands how wild Russian society is,” Zelenskyy’s adviser, Mykhailo Podolyak, said in late April.

Li arrived in kyiv on May 16 and met with Ukrainian Foreign Minister Dmytro Kuleba.

“Ukraine does not accept any proposal that would mean the loss of its territories or the freezing of the conflict,” Kuleba’s office said in a statement after the meeting, which ended, unsurprisingly, without progress.

Leave a Reply